Please join me at my new home at stevencheslikdemeyer.com. That's where I blog now. See you there!

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Not Really The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year.

The first really sad Christmas I remember was when I was I guess 21, my first year not in school, I made very little money and couldn’t afford the airfare. I don’t remember what I did that year, but it was not sitting around the tree for hours with my family listening to the Nutcracker, drinking egg nog and eating shrimp cocktail, and opening presents. My memory is fading, but I think there were two Christmases around that time in my life when I didn’t go home to Indiana.

“Home for Christmas” is not an expression I use anymore. The house where my parents lived since the mid-80s is not any of the houses I grew up in, but I thought of it in some sense as home, or it was one of the places I thought of as home — there have been many and sometimes none — but now that my mother is gone, every year it’s less home and more the house where my father lives alone. We’ll spend most of our visit at my sister’s family’s home, where I feel very much “at home,” but not “home.”

Not that any of these feelings are inappropriate to the season. The weeks leading up to the end of December are marked in different ways in different traditions, but the common thread is as ancient as humanity: we watch with dread and mourning the days grow shorter, the nights get longer. We are alone, abandoned by the sun, and we hope against hope that it will come back. When it does, we celebrate. Everything turns around. No more sadness. A new beginning. Of course we always knew it would come back, but the world still feels so empty, so bleak, until it does.

The trouble with all the other losses — your childhood house, Santa Claus, my mother — is that they are not so temporary. So the Christmas season has become less a vigil for the return of the sun than a reminder of everything that's gone long gone.

Thursday, November 2, 2017

Thoughts On Kevin Spacey.

I want to say first that I have very mixed and hard to pin down feelings about men joining the #metoo movement. Sexual harassment and assault obviously don’t happen exclusively to women. But there’s something in this moment that I think is about women’s experience, about revealing to us all a particular experience that women have in common, as a gender. So something rubs me the wrong way about so many men sharing their #metoo stories. Still, it’s complicated, and, like I said, I’m not at all confident about my feelings here.

But I want to write about homophobia and how I think there’s room for a great deal more subtlety and depth in examining how it is at work in the reactions to Anthony Rapp’s story and Kevin Spacey’s reaction to it. I am heartbroken for them both.

The thrust of the reaction in the LGBT media and community has been immediate condemnation along the lines of “We’ve been struggling forever to convince straight people that gay men are not child molesters, and you come along and tell them that in fact we are.”

But from where I sit, it looks like it is the LGBT community and media who are telling people that, not Spacey.

— Zachary Quinto (@ZacharyQuinto) October 30, 2017

Nope to Kevin Spacey's statement. Nope. There's no amount of drunk or closeted that excuses or explains away assaulting a 14-year-old child.

— Dan Savage (@fakedansavage) October 30, 2017

As recounted by Rapp, Spacey’s behavior that night was harassment, exploitation, and — depending on how you interpret the whole lying on top of him part of the story — possibly even assault. But Rapp was 14. He was not a child. Though this view is hardly universal, I personally think that an adult having sex with a 14-year-old, even with consent, is wrong for all kinds of reasons, but it is not pedophilia. If we don’t want straight people to think gay men are pedophiles, don’t say we are when we’re not.

On one level, this is an object lesson in the danger of respectability politics. It’s understandable how gun shy we are around the issue of children. When you’re called a child molester your whole life, you become incredibly self-conscious about it and you want to dig as wide a moat around it as you can to be sure you don’t get near it, you want to define it as broadly as possible to make sure you're the first and loudest to condemn it.

Of course, much of the LGBT community have resented Kevin Spacey for decades because he refused to publicly reveal his queerness, and, as so often happens when a closeted famous person is outed, the community is howling with gleeful derision. One thing, maybe the only thing, LGBT people share is the psychologically, emotionally, spiritually damaging experience of the closet. Yet there is so little empathy shown in these cases. I’ve always wondered about the causes of this ugly gay mob behavior: is it just that human trait of loving to see a successful person knocked off their pedestal?

I wish stories like these could be moments to teach straight people about how the closet distorts everything, for life. How shame corrodes our spirits. How scarred we are. Kevin Spacey is a man dealing badly, and very publicly, with the explosion of an aspect of his life that was out of control and which now seems to threaten every other part of his life. The closet is cancer. I feel deeply for him.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Spacey, but your application to join the gay community at this time has been denied."

— Dan Savage (@fakedansavage) October 30, 2017

If this is a community that doesn’t have room for the most damaged among us, then I’m ashamed of my community.

Saturday, September 30, 2017

Hugh Hefner.

Put bluntly: On one hand Hefner ushered in the ubiquity in media of images of women as ideal and willing sex objects (and all the attendant distortions for men and boys regarding expectations and consent). On the other hand, he played a big part in relaxing the shame associated with female and homosexual desire (which contributed to a massive social and legal shift for the better for women and gay people). Is it possible to extricate one from the other?

Just some thoughts.

Monday, August 7, 2017

Looking Back.

Now we are in touch again, and she’s commissioned me to write some text, an essay?, for a chapbook that she will print and publish to accompany an exhibit of her prints in Chicago where she lives and teaches now this fall. The text is to resonate with, respond to though not necessarily explicitly with the work she is showing. (She still makes visual art. I, you know, do not.) The prints span her career. One set is a series of drawings she made in 1984 in the process of working out a large installation. One set is a series of drawings in response to a large installation she made in the mid-90s.(I call them drawings -- they are monoprints.) A third set is current work.

This thing I’m writing, which I hesitate to call an essay because it is impressionistic, episodic, takes the shape of a review of our friendship (so of course it is meandering and disjointed). I’ve pulled out her letters to me spanning the mid-80s through the early 90s, half a lifelong conversation about what’s important, what we yearn for our lives to be, what we want our work to be about, the shape we want our lives to take, and I compare those hopes with how our lives actually look now. We are both still artists. That in itself is remarkable to me and something to be proud of regardless of whatever other dreams I’ve fallen short of. It was certainly never the most likely outcome, statistically speaking, but I never had any doubt and I doubt J did either.

So.

Between this project and my high school diary musical, which are the two big things on my desk right now, my writing life is thick with memory. Late 70s in Indiana, 80s in New York. It feels like judgement day up in here. When I dive into the past — I shouldn’t say dive because I more or less live there — my favorite game seems to be finding things I feel uneasy or guilty about or ashamed of and to pick them apart, to confess, and try to, if not absolve myself, understand. But, yes, absolve myself of.

It all, all of it, has the slightly queasy-making quality of a retrospective, which I supposed I should embrace. I am not done, but I am on the cusp of a new phase, I really believe. The work I am doing now is stronger, more vivid, more truthful, more true, than ever. I am 56 years old and have, as they say, zero fucks to give. A look back is appropriate. And then forward.

Sunday, July 23, 2017

Life Has Purpose.

I'm embarrassed that I've let 4 months go by without blogging. Four months!

My most valid and hopefully persuasive excuse is that I'm deep into writing a new show. Not that I'm furiously writing every second and couldn't have taken a few minutes now and then to blog, but that the energy of a new project, the mental and emotional state it requires, or maybe not so much requires but creates, distorts things around it, one of those being my sense of what else I should be doing. Sitting, staring into space is so much more compelling than really anything else. (I note that lately C, more frequently than usual, says things to me like "What's wrong?" or "Are you upset about something?" to which I say, "No, I'm just in my head.")

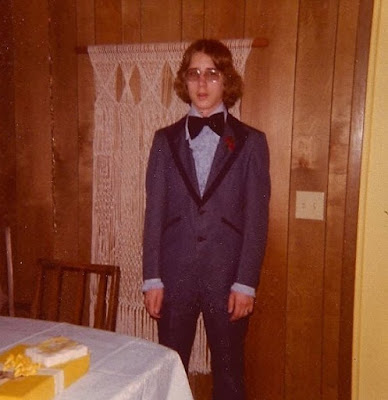

This new thing, I've probably mentioned it a few times here, is the musical I'm writing based on my high school diary. It took me a while to get oriented in it, to get some traction, but now it's cooking. I have written six songs, five of which I think are very strong, and the sixth might be great as well but I'm less confident about that one. (It is sung by a character that has been, is, I think always will be, trickier. He's a deeply unsympathetic character who I'm asking the audience to empathize with. And that empathy is kind of key to the whole thing.)

The overall shape of the show (working title is "Jack" -- my middle name and the name I was called until I left home for college) is still a bit wild and woolly but that's not as worrisome as it was a few months ago. As I work and as the story takes shape, I keep a list of "Things I Can Do Now," practical tasks like "write the song that goes there," or "write a monolog about so-and-so" and I feel good if there are 6 or 8 things on that list. When the list gets short, that's when I start to worry that maybe I'm not sure what the piece is about yet.

This show might have a female character, I'm not sure yet, but it's about boys, about men, and I'm enjoying that quite a bit, since the two other projects that have occupied so much of my time and energy for the last few years, LIZZIE and the Hester Prynne musical, are all about women. I'm sure you all know how much I love writing about women, for women, women's stories ... but men are pretty interesting, too.

And, though my own life has always played at least some part in all my writing it has often been buried, especially in the adaptations like LIZZIE and Hester, it's exhilarating --and liberating in a self-mortification way -- to be doing this explicitly autobiographical work. I can just tell the story.

So I feel energized, excited. Life has purpose.

Friday, March 10, 2017

Opposite, Both True.

I have to say I was shocked to read the New York Times's huffy review of the new Sam Gold revival of The Glass Menagerie this morning because my experience of it was so deep and powerful -- and so intimate -- that I couldn't get my head around the notion that anyone in that room could have had such a different experience. It was hard for me to imagine anyone thinking that Gold altered or tinkered with or did violence to Tennessee Williams's play. To me, this production revealed the play.

But that's just how it works, I guess. Other critics described something more in line with what I saw.

Though, as an artist, I know how personally wounding a negative review can be, when it comes to other people's work, a polarized response makes me much more interested to see something than universal praise. (I didn't really have much interest in seeing Hamilton until the backlash started which made me think there was something interesting there after all. Yes, I'm still entering that damn lottery every. single. day.)

I keep reminding myself of this as the reviews of the London production of LIZZIE roll in. Depending on whom you believe, it is either "loud, messy, and incoherent" or it is "the greatest American musical since Sweeney Todd." The critics are just about evenly split between hating it and loving it, with not much in between. It is a roller-coaster. But if this weren't my work and I were just somebody reading reviews, this would be the show I would be dying to see.

All of which is to say that the (to my mind, clueless) Times review of The Glass Menagerie pissed me off, but on the other hand left me reassured that I'm in good company.